Victory Gardens loses an ensemble of playwrights, again

Why the theater's board of directors really, really should have seen this coming.

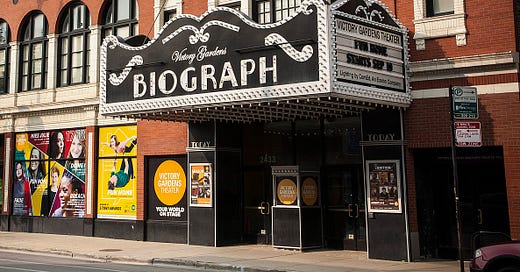

Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

Last Friday, May 22, the members of Victory Gardens Theater’s Playwrights Ensemble posted a letter of resignation on Medium. The signatories—Luis Alfaro, Marcus Gardley, Ike Holter, Samuel D. Hunter, Naomi Iizuka, Tanya Saracho, and Laura Schellhardt—made it clear that they were relinquishing their artistic association with Victory Gardens in protest.

At issue was the May 5 announcement from the theater that Erica Daniels, who had served as Victory Gardens’ executive director for three years, would be taking over artistic director duties as well. Following the December announcement that VG’s current artistic director, Chay Yew, would be leaving his post this summer, the company’s supporters had waited five months for updates on a search for Yew’s replacement.

Instead came the announcement that there would be no search, no application process, no formal consideration of candidates for the post; Daniels would take on a new dual role as part of a new executive structure, with new deputies—an associate artistic director and a general manager—to be named later.

The members of the Playwrights Ensemble wrote that they learned of this decision at the same moment it was announced to the public, and they were objecting to a lack of transparency on the part of the board:

The Board of Directors, who are of service to our community, took it upon themselves to eliminate communication with the ensemble, artistic staff, stakeholders and artists who have labored for a decade to build up this theater and its new audience.

The ensemble’s resignation came on the heels of another announcement on the day that Daniels’s new role was made public. A group of 61 Chicago theater artists—several of whom had held staff positions at Victory Gardens under Yew’s tenure—shared on social media the text of a petition they said they had sent to the theater’s board of directors on March 2, expressing concern about the radio silence regarding a search for Yew’s successor, and hinting at worries that a foothold for diverse leadership at a Chicago institution—Yew is a queer person of color leading a theater whose mission isn’t tethered to those identities—was in danger of being lost.

There’s a lot to unpack here. But one of the most fascinating aspects of the discussion, to me, is that this is the second time in a decade that the Victory Gardens board has managed to alienate an entire stable of affiliated playwrights.

It’s also not the first time in VG’s history that its board has attempted to implement a new management structure to get its way. Two decades ago, when Victory Gardens was the owner and chief resident of the four-theater storefront complex now known as the Greenhouse Theater Center, the theater’s board took an interest in buying the Royal George Theatre as a new home.

That interest was not shared by Dennis Začek and Marcelle McVay, the husband-and-wife duo who had served as artistic director and managing director, respectively, since 1977. They agreed that the theater was due for some kind of upgrade, but then-board president Hud Englehart’s desire to leap from the 195-seat mainstage at 2257 North Lincoln to the 450-seat Royal George felt like too big a step to take.

Englehart—a public relations professional who would later become senior communications strategy director in the administration of Gov. Bruce Rauner—devised a plan to outflank Začek and McVay by installing a chief executive officer, a new role that would have superseded the authority of the pair that had led the company for more than two decades.

That plan, which would almost certainly have led to Začek and McVay leaving their posts, didn’t come to fruition. When the news became public, it stoked an outpouring of objections from Victory Gardens subscribers and donors, and Englehart ended up departing from the board.

Eight years later, another board move that Začek and McVay objected to reportedly contributed to McVay’s resignation. In 2008, two years after Victory Gardens had moved into its new home at the former Biograph Theater, the company’s board voted to sell the old building—which VG had been continuing to operate as a rental facility for itinerant theaters, under the name Victory Gardens Greenhouse—to board member Wendy Spatz and her husband, William, for $2.4 million. Začek and McVay were opposed to the move but powerless to stop it; three months after the sale was announced, McVay announced her departure.

(One aspect of the deal that might have heartened McVay was a commitment that the Spatzes, as well as any future owner they might sell to, were required to continue operating the building as a theater for at least 25 years—which keeps the Greenhouse from being converted into condos or sports bars until 2033.)

Two years later, in the summer of 2010, Začek announced his own plans to retire at the end of the 2010–2011 season, while openly signaling his desire to be succeeded by his then-associate artistic director, Sandy Shinner. The theater’s board, though, didn’t immediately agree, announcing its intention to conduct a national search. As then-board president Jeff Rappin told the Tribune in 2010, “we owe it to the theater to see everyone out there.”

That search led to Yew—and to the rocky departure of Victory Gardens’ first Playwrights Ensemble. A mostly local group of 14 writers to whom Začek had been loyal for many years, the ensemble—which Začek had formally established in 1996—included names like Jeffrey Sweet, James Sherman, Claudia Allen and Charles Smith.

The company’s mission included a commitment to incubating new plays, but as with so many theaters based around ensembles of actors, it could feel like its true mission was to support these particular writers. Across the first decade of the new century, about 55 percent of the plays that Victory Gardens staged came from the 14 writers in the ensemble. Some of these playwrights were allowed to claim slots in a season based on little more than a concept—leading to scripts that would be deemed in need of further development at most theaters getting full productions.

Yew, perhaps understandably wanting to put his own stamp on the company, quietly moved the existing ensemble to emeritus status. Too quietly, in fact; some of the playwrights learned of their new status by seeing it printed in an opening-night program. “We fucked up,” Yew admitted to the Reader in 2012. The rough transition—Shinner was also shown the door (she now leads Shattered Globe, a theater whose own board once prematurely tried to shut itself down)—led to seething resentments that linger to this day among some loyalists to Victory Gardens’ old guard.

And now, a new generation of playwrights and artists nurtured under Yew’s tenure over the past decade are feeling betrayed as well. Many of those objecting to the board’s latest move are framing it as a question of process; some have been careful to say publicly that their beef isn’t with Daniels, but rather with a decision that sought neither input nor applications from the community. Others have objected to the very notion of combining an artistic leadership role with a financial one. And I believe there’s a real fear that this personnel move signals a shift away from Yew’s programming priorities.

Daniels won’t be the first theater leader in the nation, or even in Chicago, to hold the title of Executive Artistic Director. (Teatro Vista’s Ricardo Gutierrez is also an EAD.) And keeping such a rare job opening closed to aspiring candidates is legitimately frustrating. (I’ve watched several of the country’s most prominent staff theater critic positions get filled without being opened up to applicants in recent years; believe me, I get it.) As for Daniels’ artistic priorities, we’ll see, though the 2020–2021 season VG optimistically announced last month feels to me in line with Yew’s vision.

But I’m left thinking about how the board of directors thought this announcement was going to land without controversy. Through a spokesperson, Victory Gardens declined to make anyone available for comment beyond a written statement in which the board notes that “in the search for the previous artistic director [Chay Yew], the Playwrights Ensemble was not engaged in the process, nor were they in the appointment of Erica Daniels.”

The current chairman of the board, Steven N. Miller, was also board chair eight years ago when the Playwrights Ensemble that wasn’t consulted for Yew’s hiring got dumped. He should have known how this was going to go! Come on!

A theater’s board may not be legally required to include its artistic communities in major decisions, but 20 years of clashes at Victory Gardens raise the question of why people who care enough about a theater to serve wouldn’t want to include the artistic stakeholders.

Or as Steppenwolf’s Martha Lavey said to the Tribune’s Richard Christiansen 20 years ago, in the wake of the failed attempt to install a CEO to do the board’s bidding: “For the board to make this move without sufficient artistic ballast shows a lack of knowledge of theater culture. Has anybody talked to the playwrights about this? What do they have to say?”